A New Shade of Protectability

The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit recently ruled that color marks can be inherently distinctive when applied to product packaging trade dress. The CAFC upends a long-held understanding that color marks can never be inherently distinctive. Although such marks are considered inherently distinctive, color marks will likely remain a challenge to protect.

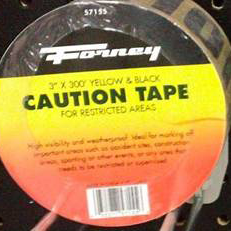

The CAFC decision was an appeal of a precedential decision rendered by the Trademark Trial & Appeal Board on September 20, 2018 in which the Board held that a color mark consisting of multiple colors applied to product packaging cannot be inherently distinctive. The case concerned an application filed by Forney Industries, Inc. for a black, yellow, and red mark as applied to product packaging, and specifically on the packing backer card, for various hardware products.

(Applied-for Mark)

(specimens of use filed May 1, 2014)

The US Patent & Trademark Office refused the application on the ground that the color mark was not inherently distinctive and that the applicant had failed to claim acquired distinctiveness as an alternative basis for registration. The Board denied Froney’s argument that its mark should be treated as product packaging trade dress, which can be inherently distinctive as decided in Two Pesos, Inc. v. Taco Cabana, 505 US 763, 770 (1992). Two Pesos concerned the registrability of the trade dress of a chain of Mexican restaurants and established the legal principle that trade dress can be inherently distinctive. In this case, Forney did not claim protection in any portion of the “trade dress” of its packaging beyond the multi-color pattern.

In denying registration, the Board did not account for any distinction between color as applied to product packaging trade dress and color as applied to a product itself. The Board reasoned that precedent dictated that color could never be inherently distinctive. See Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., 514 US 159, 162 (1995) (color may serve as a trademark provided color is not functional and the applicant can establish secondary meaning); see also Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., 529 US 205, 206 (2000) (color can never be inherently distinctive). Disregarding whether the color-based mark was applied to product design or product packaging, the Board held that a color mark consisting of multiple colors applied to product packaging without additional elements like shapes or designs is not capable of being inherently distinctive. The Board appeared to find that in the abstract, a color palette or color scheme is not capable of functioning as a trademark without having acquired distinctiveness as a mark.

A Tint of Source-Indication

Forney appealed the Board’s decision to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”). The CAFC found that the Board erred in its decision in two ways:

- the Board should have differentiated between product design and product packaging marks before concluding that a color-based trade dress mark can never be inherently distinctive; and

- by concluding that color-based product packaging marks cannot be inherently distinctive in the absence of an association with a well-defined peripheral shape or border.

The CAFC stated that the Board had essentially misinterpreted the case law concerning color-based trademarks, finding that there was no absolute principle that color-based trademarks could never be inherently distinctive. The CAFC stated that Qualitex did not expressly state that a showing of acquired distinctiveness was required for a single-color as applied to a product to be protected as a trademark. Although the court in Samara expressly stated that “one category of mark — color — can never be inherently distinctive,” the CAFC concluded that the statement applied only to product design trade dress and not product packaging. To the extent the Board’s decision suggested that a multi-color mark must be associated with a specific peripheral shape in order to be inherently distinctive was also in error.

The CAFC remanded the application to the Board to consider Forney’s mark as product packaging trade dress and to evaluate registrability under the Seabrook factors, the test for determining the inherent distinctiveness of product packaging trade dress. Seabrook Foods, Inc. v. Bar-Well Foods, Ltd., 568 F.2d 1342, 1344 (CCPA 1977). Under the Seabrook factors, the Board should consider whether the mark is:

- a “common” basic shape or design;

- unique or unusual in a particular field;

- a mere refinement of a commonly adopted and well-known form of ornamentation for a particular class of goods viewed by the public as a dress or ornamentation for the goods; or

- capable of creating a commercial impression distinct from the accompanying words.

Id.

It Paint Over Yet

Like the Board, most practitioners arguably have operated under a common understanding that color can never be protected as a trademark without a showing of secondary meaning, an incredibly high burden to meet. The CAFC decision slightly upends that understanding and provides a potentially broader scope of protection for color-based trademarks as applied to product packaging trade dress.

In an era where visual aesthetics and appeal become increasingly important in marketing a brand online and through other visual platforms, many brands rely on color as a “calling card.” Although the decision can be viewed as laying the groundwork for providing greater protections to color marks, the nature and basic character of color still carries with it a difficult burden in demonstrating distinctiveness. The Board is not without a basis to refuse registration of color marks either under the Seabrook test or on any number of other “failure to function” grounds like ornamentation, or commonly used symbols like background designs.